The following text was scanned and OCRed from the book MARTHA'S VINEYARD by Henry Franklin Norton. Copyright 1923 by Henry Franklin Norton and Robert Emmett Pyne, Publishers.

See also Tisbury (Vineyard Haven) by H. F. Norton.

ARTHA'S

VINEYARD, called "Noepe" by the Indians, which means in their

picturesque language "In the Midst of the Sea," is the largest

island on the southeastern coast of Massachusetts. It is twenty miles long

and nine miles wide and but a few feet above the sea level in the eastern

part, which is known as the Plains, one of the largest tracts of level ground

in New England. However, the land gradually rises to an elevation of over

three hundred feet above the sea level at Peaked Hill in Chilmark, not Indian

Hill as believed by many summer visitors.

ARTHA'S

VINEYARD, called "Noepe" by the Indians, which means in their

picturesque language "In the Midst of the Sea," is the largest

island on the southeastern coast of Massachusetts. It is twenty miles long

and nine miles wide and but a few feet above the sea level in the eastern

part, which is known as the Plains, one of the largest tracts of level ground

in New England. However, the land gradually rises to an elevation of over

three hundred feet above the sea level at Peaked Hill in Chilmark, not Indian

Hill as believed by many summer visitors.

Martha's Vineyard, with Chappaquiddick, No-Man's-Land, and the Elizabeth

Islands comprise the County of Dukes County, which was incorporated November

1, 1668. The county was named for the Duke of York by the first governor,

Thomas Mayhew, who was hoping thereby to gain royal favor. There are six

towns on Martha's Vineyard. Edgartown on the east, named for Edgar, son

of James II, who bore the title of Duke of Cambridge; Oak Bluffs on the

northeast, named for its location and oak trees; Tisbury for the Mayhew

Parish in England; later the village post-office was named Vineyard Haven

because of its location; West Tisbury; Chilmark, for the English Parish

of Governor Mayhew's wife, and Gay Head on the west, named for its wonderful

cliffs of different colored clay.

The first Europeans that visited Martha's Vineyard were the Northmen, who landed about the year 1000, naming it Vineland. In some of their writings have been found descriptions that can be of no other place than Martha's Vineyard.

Another discoverer of this island was Verrazano, an Italian explorer,

who first sighted the western extremity in 1524, and called it Claudia,

in honor of the mother of Francis II of France.

The next explorer, and the first one to leave any account of the island,

was Bartholomew Gosnold, of Falmouth, England. In 1602 he sailed for Virginia.

Contrary winds drove him to the Azores; thence he sailed a little north

of west, and struck out boldly across the Atlantic. He was the first Englishman

to sail directly to the American coast, thereby saving nearly a thousand

miles in distance and at least a week in sailing time. He landed on a cape

which he named Cape Cod from the abundance of codfish found there. Then

doubling the cape and sailing to the southward he landed on a small island

about six miles southeast of Gay Head. He called this small island Martha's

Vineyard. The next day he landed on the larger island. After exploring it

and finding it so large, well wooded, and with such luxuriant grape vines,

many beautiful lakes, and springs of the purest water, he transferred the

name and called it Martha's Vineyard, in honor of his mother whose name

was Martha. The other island he named No-Man's-Land.

Soon after Gosnold explored the group of islands to the northwest of

the Vineyard, naming them the Elizabeth Islands in honor of Queen Elizabeth

who was still reigning. There are eight islands in this group, named as

follows: Naushon, Nonamesset, Uncatena, Wepecket, Nashawena, Pasque, Cuttyhunk,

and Penekese. On May 28, 1602, Gosnold founded a colony on Cuttyhunk. Here

he built the first house and fort erected in New England, intending to leave

a colony there, but when he had loaded a cargo of sassafras root and cedar

logs, the settlers were determined to return with him because they were

afraid of the Indians

The sassafras root was then in great demand in England as a popular medicine

and cure-all. Gosnold counted on getting a great sum for it, but Sir Walter

Raleigh accused him of trespassing on his land, which was from north latitude

34 to 45, and seized the whole cargo, much to the disappointment and disgust

of the industrious sassafras diggers.

Referring to Gay Head Cliffs in one of his accounts, Gosnold called them

Dover Cliffs, because they somewhat reminded him of the white cliffs of

the same name in England. He found on Martha's Vineyard "an abundance

of trees and vines of luxuriant growth."

His expedition was not a failure because it showed Europe a shorter and

more direct route to America and kept up the interest in the new country.

The Mayflower followed this route eighteen years later. In 1902 a large

monument was erected to Gosnold's memory on Cuttyhunk, where the first fort

was built three hundred years before.

About five years later, in 1607, Captain Martin Pring, with a more courageous

company than Gosnold's, anchored in what is now Edgartown harbor on Whit

Sunday and called it Whitsun Bay. He built a stockade on Chappaquiddick

Bluffs which he called Mount Aldworth. Pring traded with the Indians, amused

them with music, but enjoyed terrifying them with the sound of the cannon,

and with two large mastiffs which he had on board his ship. He sailed away

at the first sign of hostility with a cargo of the precious sassafras root.

Those who attended the Tercentenary Pageant at Plymouth will remember the

scene representing Pring trading with the Indians.

By this time the Vineyard had become known to the English by the Indian

name of Capawock, and it seems to have been considered one of the most important

places on the newly-discovered American coast. This was of course because

of its geographical location, harbors and springs of purest water.

The following noted discoverers and explorers, the Cabots, Champlain, Cartier,

and Captain John Smith, must have passed through Vineyard Sound and may

have stopped for water at these wonderful springs; especially the one known

as "Scotland Spring" at the head of the Lagoon Pond.

AVING considered the discovery and exploration of the island let us

now turn to the early settlers and their work which largely contributed

to make the Vineyard what it is to-day.

AVING considered the discovery and exploration of the island let us

now turn to the early settlers and their work which largely contributed

to make the Vineyard what it is to-day.

Tradition tells us that there were families living here by the name of Pease,

Vincent, Trapp, and Stone before 1640. The story goes that these settlers

were on their way to join the Jamestown colony , but were driven into Edgartown

harbor for shelter. They remained here after spending their first winter

in a dugout at "Green Hollow," near what is now known as Tower

Hill. This story seems reasonable enough but history contradicts it as some

of these families were living at Watertown, Massachusetts.

Thomas Mayhew, an English merchant and a settler of Watertown, Massachusetts, not far from Boston, bought in October, 1641, from Lord Stirling and Sir Ferdinando Gorges, through their agent James Forcett, the islands of Martha's Vineyard, Nantucket, and the Elizabeth Islands. Lord Stirling and Sir Gorges having received their right of ownership from the English Crown.

The same year, Mayhew sent his son Thomas, with a few families to settle

on his new purchase. They landed at a place they called "Great Harbor,"

later named Edgartown. The place of landing is not definitely known but

there is reason to believe that it was between Collins's wharf and Tower

Hill. Young Mayhew compelled all his company to purchase their lands from

the Indians. We can find in the old records at Edgartown where the first

settlers had their grants of lands, for many of the deeds are written in

the Indian as well as the English language. The following year, 1642, Governor

Thomas Mayhew came to the Vineyard with other settlers. He brought domestic

animals, tools, and many things which were needed to start a new colony.

Among the families that were here in 1650 we find the names of Butler, Bland,

Smith, Burchard, Daggett, Folger, Bayes, Trapp, Norton, Pease, and Vinson.

Thomas Mayhew, Jr., the only son of Governor Mayhew, was the first missionary

to the Indians of New England. He was a graduate of Oxford, a good Latin

and Greek scholar, and was familiar with the Hebrew tongue.

After the arrival of his father, young Mayhew found the English flock small.

The sphere was not large enough for so bright a star to move in, so he commenced

his work among the Indians. He worked diligently, and the first Indian who

believed in the true God was Hiacoomes who lived not far from Great Harbor

and used to attend the meetings of the English. First he stood outside and

each Sunday came a little nearer. After a few weeks he dared to enter and

take a back seat. Soon the Indian and the young missionary became fast friends.

At the end of the first summer Hiacoomes and his whole family were attending

the white man's church. During the second winter a terrible fever broke

out among the Indians and many of them died. The family of Hiacoomes was

not afflicted. Mayhew took this opportunity to preach a sermon from the

ninety-first psalm, "There shall no evil befall thee, neither shall

any plague come nigh thy dwelling. For he shall give his angels charge over

thee, to keep thee in all thy ways." At this time Hiacoomes joined

the Church of Christ, the first Indian on Martha's Vineyard to give up the

worship of the false gods.

After this Mayhew spent considerable time with his new convert learning

the Indian language. In a short time he had mastered the Indian tongue so

that he was able to hold meetings at the wigwam of Hiacoomes. After that

his Indian converts became more numerous. A few years later we find young

Mayhew traveling all over the Vineyard preaching to the Indians and telling

them of the wonderful works of God in their own language. He would spend

half the night telling the Indians and the children Bible stories. In order

to strengthen his teachings Mayhew was accustomed to question the Indians

on the principles of religion so as to make sure that they understood his

doctrine.

This young man of twenty-four may be pictured with his Indian band beside

the lake at Tashmoo, by the waters of Quatapog, on the great cliffs at Gay

Head, explaining to them the songs of David, with God's handiwork all around

him and the spirit of the Great Master within him.

January 11, 1651, Thomas Mayhew, Jr., established the first school on

Martha's Vineyard to teach the native children and any of the young Indian

men who were willing to learn. He hired Peter Folger to become the first

teacher. Folger later became the grandfather of Benjamin Franklin, and his

descendants still make their home on the island. Folger found the Indian

"very quick to learn and willing to be instructed in the ways of the

English."

In 1657, in his thirty-seventh year, young Mayhew proposed a short trip

to England in order to give a better account of his work among the Indians

than he could by letter. He also planned to purchase books and to bring

back ministers and teachers to help him carry on his work.

He spent his last week with his Indian converts. While at what is now Farm

Neck the Sachem of Sanchakantackett gave him a big "powwow." After

the dinner Mayhew praised the good split eels for which that neighborhood

is famous. The Sachem said: "Mr. Mayhew, him no eels, him black snake

from big swamp; no venison, him my best dog me kill for you." Whether

or not young Mayhew enjoyed the feast may be left to the reader. In any

event it showed that the Indian thought a great deal of him and the best

dog was none too good for him.

Mayhew's last meeting with the Indians before he sailed was held at a place about half-way between Edgartown and West Tisbury known as "The Place on the Wayside." Here all the Indian converts met him, about fifteen hundred in number. The chiefs and all their tribes came and formed a semicircle about the place where Mayhew was to stand. Many of these Indians had followed him from Gay Head as he came down towards Edgartown. The service was opened with prayer by Mayhew. Then he preached to them, taking his text from the first and twenty-third psalms: "He shall be like a tree planted by the rivers of waters, that bringeth forth his fruit in his season; his leaf also shall not wither; and whatsoever he doeth shall prosper." "The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want." A song was sung. He gave his Indians unto the care of Peter Folger; another short prayer and then the farewell. At the close, Hiacoomes came forward and shook the hand of his beloved teacher, and, bursting into tears, placed a white stone at his feet, saying: "I put this stone here in your name and whenever I pass, here I shall place a stone in your memory until you return." Mayhew answered; "Hiacoomes, not in my name, nor in my memory; but in the name and memory of the Great Master of whom I have taught you, Christ." All the chiefs placed a stone where Mayhew stood, and throwing their blankets over their faces and with their heads bowed in grief, followed by their tribes, marched in Indian file over the Plains to their homes.

The next morning Mayhew sailed, taking with him his wife's brother, and

the first Indian graduate of Harvard college, who was a preacher among the

aborigines. The Indians stood on the beach with bowed heads as the ship

sailed and the Indian runners followed as far as they could. Alas, the mysterious

ways of Providence; neither the ship nor its passengers were ever heard

from again. Young Mayhew's name was never mentioned without tears and as

one who expected no reward but from Him who said: "Go teach all nations,

Lo I am with you."

When the writer was a young boy his family had an old Gay Head Indian woman

working for them. She was planning to go home, for a short visit and he

was to take her as far as West Tisbury where she could get the stage for

Gay Head. Just before starting she asked him if he would go by the Indian

trail along the South Side. She picked up a white stone, put it in the wagon

and they then started on their trip.

At that time the writer knew nothing about "The Place on the Wayside"

but as they neared it she told him how, when she was a little girl walking

with her grandmother from Gay Head to visit her people on Chappaquiddick,

they had stopped and placed a stone in the memory of the Saviour, and the

first white man who had taught them to know Him. When they came to the place

she got out of the wagon and placed the stone on the pile which must have

been between three and four feet high. She said a short prayer and returned

to the wagon.

As the writer looks back and sees that old Indian woman, the granddaughter of the last Sachem of Gay Head, and the great grand-daughter of the last Sachem of Chappaquiddick, placing her tribute on that pile of stones, the place becomes Holy Ground. What grander monument could one wish than to have a stone placed to his memory two hundred and forty years after by the Indians because of his work among them!

The writer has stood on the rock in Farm Neck where Thomas Mayhew, Jr.,

preached to the Indians of Sanchakantackett. He also attended the dedication

of the Mayhew monument at "The Place on the Wayside," in 1901.

This monument was a boulder given by the Indians of Gay Head. The Martha's

Vineyard Chapter, D. A. R., had a bronze tablet placed on the boulder telling

the story of young Mayhew's work and death. Since the dedication in 1901

the greater part of the original pile of stones has been removed by souvenir

hunters.

"PLACE ON THE WAYSIDE"

The links by which our storied spots are chained,

Fast riveted by years of brilliant dreams,

Ambitions spent and hopes, perhaps attained,

To present hours reflecting brightest gleams

Of deeds benevolent, heroic, grand,

Are varied as the matchless tints of flowers,

The glittering gems on oceans whitened strand,

Or blending glories charming sunset hours.

Beyond two centuries and more, I look,

As in a picture, scene, historic view,

And plainly see, as in an open book,

The younger Mayhew and his foll'wers true;

Long lines of dusky Indians come to clasp

The friendly hand of him whose teachings pure

Had turned their minds from war's revengeful grasp

To thoughts of Christ, and peace that should endure.

They sadly stood in oaken grove divest,

A little while ago bedecked in gayest green,

And wooing sweet the birds from winter nest,

To cradle soft, its leafy boughs between.

The lonely hills inclined to cloudy sky,

And drear and brown the heath-clad plains;

November's chill and portent gloom are nigh;

And homeless birds are singing sad refrains.

O mem'ried stones, with saddest word "Farewell,"

Impressed, in fancy, by such tearful grief,

Not pean grand, nor solemn dirge can tell,

The love, the trust, the simple heart's belief

Conveyed to them through him who kindly taught

To native souls the message Christ imbued,

As one by one the stolid Indians brought

A stone unpolished, but with tears bedewed.

As sped the years, the spot was holy ground,

To all that band of Indian converts bold,

And not a man among them could he found,

So freed from credulous belief of old,

Who dared when passing mystic spot enshrined,

In tedious march or chase for forest game,

Forget the symbol with its love entwined,

But placed thereon a stone in Jesus' name.

Since that event whose story we recall,

The Indian darts at white men swiftly hurled;

The wars that freed our land from England's thrall,

And saw the minute man amaze the world;

The strife in which a Worth, to victory led,

The war for Slave in which our fathers fell,

And the world's conflict bringing sadness, dread,

Have made and kept our nation's freedom well.

The patriotic fires that ever glowed,

In sires of Revolutionary fame,

Have lately gained a fav'ring sure abode,

In hearts of daughters, hundred race and name;

Who backward glance to dreary primal days,

To time when feet of white men rarely trod

The wave-lulled, sandy beach, or sylvan ways

Where wordless music raised the soul to God.

As poet, we will loudly cry, O save!

And let no touch of blasting hand consume

These stones, with which rare memories pave

This place of parting and of deepest gloom,

O forest dark o'ercapped by cloudlets white

Whose tranquil beauty slow unfolding rose,

Attested ye, on Martha's Vineyard's site,

How simply savage hearts in Christ repose.

Place on the Wayside! In seclusion sweet,

Thy name in mellowed light of years is known;

The tablet's lasting bronze will now repeat

The honor claimed for Mayhew quite alone

And clinging vines, in wildness Nature owns,

Shall intertwine as years fast glide away,

To hallow all the sacred mem'ried stones,

That lie in silence by the woodland way.

GOVERNOR MAYHEW CONTINUES SON'S WORK

After the death of his only son, Governor Mayhew, although in his sixty-fifth

year, took up the work among the Indians, preaching to them one day every

week as long as he lived. Sparing no pains or fatigue, sometimes walking

twenty miles through the woods to Gay Head, to carry on the noble work commenced

by his son.

Though the loss of his only son was a great sorrow to him, Governor Mayhew

lived to see a son of that son associated with him in the Indian service.

This man was Rev. John Mayhew, whose son Experience and grandson Zachariah

Mayhew were great missionaries to the Indians of Martha's Vineyard. After

the death of Zachariah Mayhew the work was taken up by Rev. Frederick Baylies.

August 22, 1670, the first Indian church was organized. The famous Mr.

John Eliot was prcscut, for in a letter published at London in 1671 he writes:

"Passing over the Vineyard many were added to the church, both men

and women. The church was desirous to have chosen Governor Mayhew, but he

waived it." Mr. John Cotton of Boston was hired to carry on the work.

Governor Mayhew died at the age of ninety-two. His death was greatly lamented

by both the English and the Indian. The Indian had always found a father

and protector in him, for he made it evident to them that he did not rule

by self-will or humor, but by wisdom, justice and reason. It was for this

reason that during the Indian Wars this island was guarded by the Christian

Indians.

Governor Mayhew requested that his grave should not be marked, so at this

time the question has come up as to the place where the Governor rests.

Without doubt he was buried in what is now Collins's back yard near a large

black stone. Governor Mayhew's home was only a short distance and his favorite

grandson Mathew Mayhew and family are buried near this spot.

Before leaving the story of Governor Mayhew, perhaps it might be of interest

to mention an old deed which was found in the Edgartown records, reading

as follows: "I do sell the island of Nantucket for thirty pounds Stirling

and two beaver hats, one for my wife, and one for myself."

To-day the race has become extinct in all the portions of the fair island where young Mayhew dwelt and worked; a few scant remnants alone survive about the painted cliffs at Gay Hcad. Old deacon Simon Johnson, the last full-blooded Indian, is remembered only by our oldest inhabitants. The last wigwam fell into decay on the slopes of Sampson's Hill long ago. They sleep in unknown graves; their names are for gotten. No chronicle of their lives can ever be written, but they have left us a stainless memory. A pleasant heritage they have bequeathed us, of sweet sounding names for our hills, ponds and many quiet nooks.

Chappaquiddick becomes holy ground, made forever sacred by the loving

toil of Hiacoomes. Its air is resoundant with the prayer and praises of

the God-fearing people who have built their wigwams and their meeting house

in its quiet retreat. Nashmois, Tashmoo, Ahquapasha, Pohoganot, Mattakessett,

Sanchakantackett, Quansue, Scribnocket, and all the rest of these pleasant

places are invested with an intensely human interest by the remembrance

of the good and true lives lived here by the Christian Indians.

Reach back over the centuries to give a clasp to the Indian as our friend

and brother. We are constrained to say, had there been Mayhews to deal with

the fierce Indians of the mainland, had the Pequot and the King Philip people

experienced the happy lot of the Vineyard Indians in their contact with

the white men, there would have been no Swamp Fight, no Bloody Brook, and

the burning of Deerfield, and all the unspeakable horrors of King Philip's

War, and French and Indian Wars would have been unknown. The Indian would

have proved himself everywhere a kindly, well-disposed person, susceptible

to the fine influences and capable of sustaining an honored place amid the

great families of the world.

HE early colonists that came to the Vineyard found the island well adapted

to grazing and agriculture. The climate was mild in comparison with the

other New England settlements. The island was well-wooded, chiefly with

oak and pine, sufficient for all building purposes. Sawmills were soon established

and homes built. One of the first houses built in what is now Oak Bluffs

was built at Farm Neck by Joseph Norton before 1670. It stood near the half-way

watering place on the highway that leads from Edgartown to Vineyard Haven.

A description of this house will apply to nearly all the houses built at

that time. With two or three exceptions they were of one story; large on

the base and low in the post. They were always located near springs of fresh

water, or where water could be had by digging shallow wells at which old-fashioned

sweeps could be used. Another interesting fact is that near the site of

these ancient dwellings can be seen old pear and cherry trees, which tradition

says were planted soon after these houses were built The frames of these

houses were of oak and pine which grew near. There was a saw pit he the

neighborhood, to which these great trees, many of which were three feet

in diameter, were hauled by oxen and sawed into convenient dimensions by

hand, one man in the pit and another above.

Foundation and cellar walls were of old field stone; one hardly, if ever,

finds a stone that has been split by drill or wedge. The chimneys were very

large, many eight feet square at the base, made of crude bricks burnt in

the neighborhood The lime used to make the mortar was as of the very best

quality, made by burning oyster, clam, and other shells found along the

shores. Specimens of it are as hard as rock at the present time. Another

kind made mostly of clay was used where it didn't come to the weather.

The rooms were arranged conveniently for use, a small front entry, with stairs leading to the chamber from it. Two large front rooms to the right and left, usually sixteen or eighteen feet square, and always on the southerly side of the house. The panel work over the fireplaces in these rooms was very elaborate and is now considered worthy of preservation. The "beaufat" must not he forgotten as it was the receptacle for the best china and silverware which the house afforded. Next was the large kitchen in the rear, with its fireplace eight by six feet, in the center of which hung the trammel used to hold the great kettle for the cooking of the savory meals for the large families of those days. To the right and left of the kitchen were four rooms used for sleeping and storerooms. The "up stairs part" of the house was divided into two sleeping rooms and the "open chamber," which was used for storing everything from the India shawl to grandfather's chair. This was also used as the spinning and weaving room, for the housewife made all the cloth and linen used by the family.

It is interesting to observe the fine quality of lumber used in the outside

finish; handmade shingles on the upright two feet long and good after a

hundred and fifty years weathering. The nails were of the best hammered

iron. The old wide boards were called "Bayboards" because they

came from Buzzards Bay.

These early homes were lighted before 1700 by the light of the fireplace

and burning of large pine knots of the fat pitch pine trees which grew here

in abundance All the settlers kept sheep and oxen, and the tallow from these

animals was made into candles by hand at first, known as dip candles Later

they were made by molds. Later the tallow candles were abandoned for sperm

candles made from oil from the sperm whale. The largest sperm candle factory

in America was at Edgartown. Still later the sperm candle was given up for

the sperm oil lamp These lamps were made of pewter, brass and glass, and

are much sought after by the "Collector of the Antique."

In looking over the pages of the history of our country we find that one of the first things the colonists did after they had founded a church and a government was to establish a school. Five years after the coming of the Puritans at Boston the Boston Latin School was established, and the following year Harvard was founded by John Harvard. Many instances could be related where the school was one of the first organizations. It has already been told how Thomas Mayhew, Jr., established the first school in 1651 to teach the Indian. Long before that date there had been a school to teach the English children.

In the early part of the eighteenth century there was a law passed that every town with fifty families should establish a public school. At that time public schools were established at Edgartown, Tisbury and Chilmark. In September, 1748, a town meeting was held in Tisbury at which it was voted to have a "moving school," in the following manner: "In the first place to be kept at Holmes Hole, now Vineyard Haven, two months beginning in the fall; then at Checkemmo school-house for three months; then at a place called Kiphigan for two months; then at the schoolhouse near the meeting house at Tisbury, now West Tisbury, for five months" It also provided that the whole town should have full and free liberty to send their children to any of the said places for schooling without molestation throughout the whole year if they or any or all of them saw fit. The best school of the eighteenth century and the first part of the nineteenth was kept by "Parson Thaxter" at Edgartown. Scholars attended this school from all of the neighboring islands. Under "Parson Thaxter" many of the Vineyard boys were prepared to enter college, and Latin was studied at the age of seven.

Rev. Joseph Thaxter was pastor of the Congregational Church at Edgartown

for nearly fifty years and was always spoken of as "Parson Thaxter."

He was the first chaplain of the United States Army. On the fiftieth anniversary

of the "Battle of Bunker Hill," Josiah Quincy says: "The

first exercises of the day had a peculiar interest. The occasion was of

course to be consecrated by prayer, and venerable Joseph Thaxter of Edgartown,

chaplain of Prescott's own regiment, arose to officiate. Fifty years before

he had stood on the same spot, and in the presence of many to whom that

morning sun should know no setting, called upon Him, who can save by many

or few, for His aid in the approaching struggle. His sermon brought the

scene vividly to the view of all those present."

In imagination they could almost hear the thunder of the broadside that

ushered in that eventful morning. They could almost see Prescott and Warren

and their gallant host pausing from their labors to listen to an invoca

tion to Him before whom many would appear before nightfall. They could almost

realize what thoughts filled the minds of the patriots before that decisive

conflict. How things have changed since then. All except the Being before

whom they bowed, God alone is the same yesterday, to-day and forever.

In 1825 the Thaxter School was dedicated as Thaxter Academy, with Hon.

Leavitt Thaxter, son of "Parson Thaxter," as principal.

Another school was the Davis Academy, located diagonally across the street

from the Thaxter Academy. This school was conducted by David Davis of Farmington,

Maine.

There was also an academy established at Vineyard Haven by Deacon Nathan

Mayhew. The students were called to school by a piece of steel in the shape

of a triangle; this was struck with a hammer and the sound would travel

a long distance. This building was bought by the Sea Coast Defense Chapter,

D. A, R., and is used as an historical building.

In the early part of the last century many private schools were kept. Some

of the following teachers will be remembered by the older inhabitants: Maria

Norton, Catherine Bassett, Emily Worth, Frances Mayhew, and Jedidah Pease,

known to this day as "Old Jedidah Whipper."

It seems, because of the scarcity of money, to have been the custom among

the Vineyard people during colonial times to barter, not only with their

neighbors but with ships that came into the harbor. The pilot would exchange

home-made mittens, cookies, pies and other things for molasses, sugar, ginger,

spices and Holland rum. The housewives of Eastville and Edgartown were rich

in supplies of all kinds. Coal was burned at Eastville before they ever

had it at Boston.

The shoemaker would exchange his home-made shoes for wool, mutton, beef

or whatever he wanted which the farmer had on hand. The blacksmith would

do the same. Mr. Dexter, a blacksmith at The-Head-of- The-Pond, did iron

work for a farmer and received in payment two fat goats, two bushels of

rye, corn and pine timber.

UNE 20, 1775, a general notice was given to all the inhabitants of Martha's

Vineyard to turn out and assemble at Tisbury on June 25th to see what measures

should be taken because of the Island's exposed position. There was a large

majority in favor of applying to the General Court at Boston for soldiers.

At this meeting all their arms were inspected. The next step, as expressed

in the quaint language of the period, was: "To sound the minds amongst

the young men to see who would join the volunteer corps of Edgartown."

They soon found that nearly all were ready.

UNE 20, 1775, a general notice was given to all the inhabitants of Martha's

Vineyard to turn out and assemble at Tisbury on June 25th to see what measures

should be taken because of the Island's exposed position. There was a large

majority in favor of applying to the General Court at Boston for soldiers.

At this meeting all their arms were inspected. The next step, as expressed

in the quaint language of the period, was: "To sound the minds amongst

the young men to see who would join the volunteer corps of Edgartown."

They soon found that nearly all were ready.

The first act of the Revolution that stirred the ''Islanders'' was the attempt

of the enemy to plunder the few houses on the Elizabeth islands.

When independence was declared by Congress in 1777, an order came from the

General Court at Boston to the several towns in the Province located on

the Vineyard to assemble, and for the inhabitants to give their opinion

on this very important transaction. On this occasion one of the towns would

not even meet, and the other two at their meetings positively refused to

act on the matter.

It was for their own good to stand neutral because of their exposed position; but they were willing to send all their men to fight with Washington, for there was not a battle of the whole war from Bunker Hill to the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown in which a Vineyarder did not take part and do his duty. One of the leading citizens of the time expressed the whole matter as follows: "The British come here and pay you good prices for your sheep, cattle and provisions. You can take this money and help our army in many ways. If you refuse they wilt take everything as they can land anywhere, anytime, and you haven't any way to protect yourselves." This was said at a town meeting. The citizen was called a traitor, and a vote was passed to hang him. He looked up with a smile and said: "Here I am, boys. You will find that I have told the truth sometime." They let the matter drop. Later the Vineyard openly declared herself for the cause of liberty.

September 10, 1778, General Grey in command of a transport of eighty-two

sails and ten thousand British troops made a raid upon the Vineyard, carrying

off all the sheep, swine, cattle and oxen that could be found. To oppose

this wholesale spoliation the "Islanders" had no power so they

submitted in sullen and despairing silence, at times even assisting to drive

away the captured flocks, hoping thereby to prevent still greater waste

and outrage. A very good idea of this period is given in the diary of Colonel

Beriah Norton, which reads as follows:

"September 10th. -- Gen. Grey commanding a detachment of his Majesty's

army arrived at Martha's Vineyard, when I waited on him on shipboard. Agreed

to deliver him 10,000 sheep, 300 head of cattle; the General informed me

that payment would be made for the same if they were not resisted. The General

then required the stock to be brought to the landing the next day, which

was punctually complied with.

"September 11th. - This day the troops landed under the command of

Col. Sterling. Said Sterling then informed me that Gen. Grey had directed

him to assure me that the whole stock would be paid for if they came down

according to the conversation of the evening before. Sterling then informed

me that a person must be appointed to appraise the stock before they would

take any on shipboard. To which I agreed and we jointly agreed to. I did

appoint proper persons to do that business; who were sworn by me to do their

duty faithfully by the request of Col. Sterling. The stock was by this time

coming down to the landing and was taken on board to the amount of 10,000

sheep and 312 head of cattle.

"September 14th. - Col. Sterling then informed me and other inhabitants

of the island that he had a message to deliver to the people. Then he recommended

them to meet in a field for there was not room for them in doors, accordingly

they met to the amount of several hundred. He informed us that we were to

apply to New York for payment for the stock that they had received. I asked

the Colonel if we best send a man in the fleet at this time for the payment

to which the Colonel replied, we might if we chose but he recommended us

to wait a little time before application was made.

"September 15th. -- The fleet sailed for New York."

It must seem to the reader that this Colonel Beriah Norton was a traitor

to his own people, but what could he do but give in to Grey's command! Grey

had the force and the power and could have destroyed the towns on the island

in half a day, and would have done so if they had resisted in any way. In

the diary, September 12th and 13th are omitted. Those were the days when

the British troops were ravaging the island from Edgartown to Gay Head.

A man was sent to New York to receive payment for the stock, but Grey had

forgotten that he had ever stopped at Martha's Vineyard. Colonel Beriah

Norton made two special trips to London for the same purpose, and at one

time he was given a hearing in Parliament. Very little was accomplished

in these two trips to England.

Whale fishing was carried on by the Indians long before the arrival of

the white men. After the whites came whenever a dead whale was washed ashore

the Indians always claimed a share. In many cases when Indians sold land

they reserved a certain "whale right" on all whales that drifted

ashore, and also the "rights to fish and whale."

All Vineyard boats in its early history had a number of Indians among the

crews because they knew the habits of these fish and could manage the boats

while the fierce struggle was going on.

When Captain John Smith passed through Vineyard Sound in 1614 he saw: "mighty

whales spewing up water like the smoke of a chimney, and making the sea

about them white and hoary."

John Butler was the first known whaler of Martha's Vineyard. He was an expert

for, at times, he killed seven or eight whales a month.

The first whaleship on record that sailed from the Vineyard was the schooner

"Lydia," with Peter Pease as master, which left Edgartown for

a voyage to Davis Straits in 1765.

Before this time whales were plentiful about the shores. Men would go out

in small boats and capture them. After a while all the whales near the island

here caught, and the men were obliged to go farther and farther away from

home, until finally they were compelled to go on voyages lasting from three

to five years. In 1850 Vineyard ships commanded by the brave and hardy sons

of this island were found on every ocean of the globe. Wherever whales were

to be found they were very sure to feel the harpoon thrust to their vitals

by a Vineyard arm. Fifty ships were fitted out at Edgartown at one time.

In those days the Port of Edgartown was one of the most important on the

coast, having its own custom house and doing thousands of dollars worth

of business. Ships from all parts of the world came there for clearance

papers and to pay the duty on cargoes. In 1850 whalebone was worth twelve

cents a pound; now it is worth from three to five dollars a pound.

Now when a captain or officer goes on a whaling voyage he packs his trunk

and takes the train for San Francisco where his ship or steamer is ready

for him. He starts for the Arctic Ocean about the first of May, where he

remains about three months returns to San Francisco and arrives back in

Edgartown about the first of October. Many Vineyard women, the. wives or

daughters of whaling captains, have dared the dangers of the whale fishery,

and there are women living on the island today who can tell tales of adventure

that have happened under the sum of the equator or beside the ice floes

of the Arctic.

The Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 nearly ruined the whale fishery;

but when we had gained "The Freedom of the Sea" a new fleet of

whale ships was soon built.

There is hardly a cemetery on the island but what has a stone to the memory

of some dear husband, father or son, with the inscription "Lost at

Sea." The first gravestone on the Vineyard so marked is at Lambert's

Cove, with the inscription, "To the memory of Anthony Luce, March 20,

1769, aged thirty-six years."

Until a few years ago there was a cemetery in the field between the Marine

Hospital at Vineyard Haven the old Edgartown Road where one could find a

slate stone with the following epitaph:

"John and Lydia that lovely pair,

A whale killed him, her body lies here,

There souls we hope with Christ now reign,

So our great loss was there great gain."

Someone had the graves and stones moved from this lot to the Oak Grove Cemetery at Vineyard Haven.

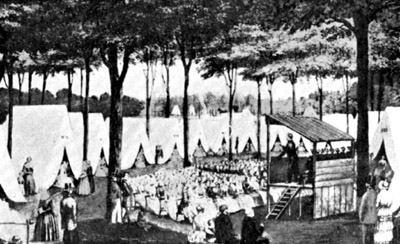

Perhaps one of the quaintest institutions on the Vineyard is the Martha's Vineyard Camp-Meeting Association. The first camp-meeting commenced Monday the twenty-fourth of August, 1835. A meeting has been held every year since excepting the year 1846. In 1836 what is now Oak Bluffs was a sheep pasture, and the huckleberry brush was so thick that one could hardly get through. The ministers and congregation landed at Eastville, and walked or rode in ox-carts to a place called "Wesleyan Grove," where the tabernacle now stands.

Only nine tents were erected at the first camp-meeting, making a semicircle,

in front of which they had erected a stand of old boards and drift wood,

which was called the "preacher's stand." The congregation sat

in the open air on split trees with pegs driven for legs. There were nearly

three hundred at this meeting. These first meetings were very simple and

unique in form. Each succeeding year they assumed larger proportions until

they became the most fully-attended meetings of their kind in this country.

From these few tents, which were later boarded in to make summer cottages

the town of Oak Bluffs grew, until now it is one of the best-known watering

places on the northern Atlantic coast.

The town grew fast, and in 1874 a railroad was built from Oak Bluffs wharf

to Edgartown, then to Katama and on to South Beach. The first train was

run over the road on the twenty-second of August of the same year. This

road was kept in operation until 1897.

About 1890 a horse-car line was started at Cottage City, now Oak Bluffs.

This line commenced at Oak Bluffs wharf, extending to the Prospect House

at Lagoon Heights; another branch went through the Camp-ground and on to

New York wharf. Later electric cars were used and the line was continued

to Vineyard Haven. This was discontinued in 1917 and the rails were sold

to the government for old iron.

The following celebrated people have visited the Vineyard: John Eliot,

the "Apostle," in 1670. John Adams, later President, visited his

college chum Jonathan Allen at Chilmark in 1760. John Paul Jones in 1777

took refuge in the harbor of Holmes Hole after a fight with a British ship,

and obtained medical aid for two of his wounded sailors. From 1835 to 1850

Daniel Webster visited Dr. Daniel Fisher at Edgartown. Whittier, Hawthorne,

and Charles Sumner were frequent visitors. In 1874 President Ulysses S.

Grant came to Oak Bluffs. Agassiz and Alexander Graham Bell were here at

different times.

In 1876 Lillian Norton sang for the first time at Edgartown, the home of

her ancestors. In 1908 she came to the Vineyard as the world's greatest

interpreter of Wagnerian operas, at this period known as Madame Lillian

Nordica.

The Vineyard has always done its part in the wars that have kept this country

free. In the War of 1812 we find that her men were in command of privateers

and on all the leading ships of the navy. Some of the men were in Dartmoor

prison, England, and two died there. Major-General William J. Worth, a man

who spent his boyhood days at Edgartown, took a prominent part in the Mexican

War. In the Civil War the Vineyard furnished two hundred and forty soldiers

and sailors, filling its quota at every call of the President. In the Spanish-American

War four boys enlisted from Oak Bluffs, namely: Herbert Rice, Morton Mills,

Manuel Nunes and Stanley Fisher. In the World War the Vineyard more than

filled its quota at every call, and Gay Head sent the largest number of

men according to population of any place in New England

The writer has endeavored to give a brief and accurate sketch of the history

of Martha's Vineyard, by touching on the main points and giving an idea

of its colonization and inhabitants who have helped to make the Vineyard

what it is todaya prosperous, flourishing community of God-fearing citizens,

who are trying to carry out the wishes and desires of those great and humane

men who together with the Pilgrim Fathers dared the cold and inhospitable

New England climate.

"From out of thy rude borders have spread far and wide

Thine own sturdy sons, once thy joy and thy pride.

To fell the thick forest, to plough the rough main,

To gather bright laurels of glory and fame."