Main Street, Vineyard

Haven, MA: The

Bank to Union Street

Site 1: Part Two - The Great

Fire of 1883

The following is Part Two of a history of the buildings and businesses

that once stood where Compass Bank stands today, on the east side of Main

Street in Vineyard Haven, Mass. This segment relates to the Great Fire

of 1883.

This is an unfinished draft! Do you have any memories of any of the

other people, places, businesses or events mentioned here? Or do you have

corrections, additions, or suggestions? Please contact Chris Baer <cbaer@vineyard.net>

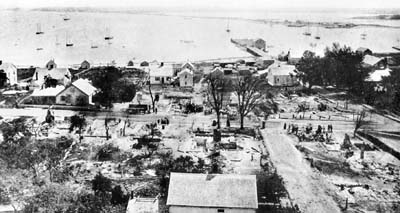

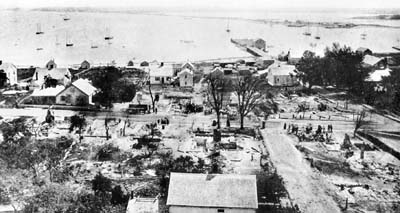

Part of the aftermath

of the 1883 fire. This photo was taken from the location of the modern

Linden Tree, looking northwest.

Part of the aftermath

of the 1883 fire. This photo was taken from the location of the modern

Linden Tree, looking northwest.

Site 1: Part Two - The Great Fire of 1883

Stan Lair said: "The Martha's

Vineyard National Bank was the former site of the harness factory owned

by Rudolphus Crocker, and it was the start of the 1883 Fire that destroyed

all of Main Street. My mother described it as 'a day that had no night.'

It completely destroyed both sides of our Main Street, including the old

Mansion House."

The 1883 fire was no surprise to many residents of the village, who long

complained about the lack of fire-fighting equipment in town.

A Vineyard Haven correspondent for the Gazette wrote

in January 1873:

"We are absolutely at the mercy of a fire. There are no appliances

for extinguishing fires in the place, and considering the frequency of

terrible conflagrations, the apathy of our citizens upon this subject is

one of the strangest things on record."

The following month, Vineyard Haven correspondent "S.N.N."

reiterated:

"The village is absolutely at the mercy of a fire, the only apparatus

for extinguishing fires being a few antiquated fire buckets, widely scattered,

and a dozen or so force pumps - mere syringes. …"

A decade after S.N.N.'s comments appeared in the paper, their prediction

came to fruit. The fire started on the north side of town on the evening

of August 11th, 1883 and proceeded to burn down all of Main Street from

Nye's paint shop to the Mansion House and beyond, on both sides of the street.

Flying, burning shingles also started two isolated fires on William Street.

The New Bedford Evening Standard reported afterwards:

"It may seem strange to many that there was so little insurance, only

a third of the total amount of loss, though the latter figure is considerably

exaggerated in the detailed reports, especially the stocks of goods in

dry goods stores, which could not have been much more than half what was

represented. Considering the fact that there was no fire department, insurance

rates were low, generally 1¼ to 2 per cent. for five years on dwelling

house property and closely adjacent to other buildings, and nothing over

2 per cent. per annum in the thickest business section. And yet people

did not get insured. And why should they? It was eighty years since a dwelling

house in the village had been burned, and nobody expected that any more

would ever be burned. About twenty years ago two houses were burned situated

a quarter and half a mile out of the village respectively."

The fire, the most destructive ever in the history of Martha's Vineyard,

made the front page of newspapers from New Bedford to Boston to New York

City. Social correspondents from many regional newspapers had been staying

in Cottage City, which was enjoying a broad surge in popularity as a summer

resort for urban, wealthy off-islanders.

The fire was discovered about 8:45 p.m. on a Saturday evening at Crocker's harness factory, which was immediately enveloped

in flames. Vineyard Haven had no fire department, and virtually no fire-fighting

equipment, but the village did have a single telephone at the grocery store

of Stephen C. Luce (see Site #29),

and so a telephone call for help was placed to Cottage City.

An article written for the Gazette in August 1933 on

the fiftieth anniversary of the fire noted:

"There was a concert at Cottage City when the solemn church bells

clamored out the alarm. A man stepped on the stage and recommended calm."

'You are in no danger,' he said. 'The fire is over in Vineyard Haven.'

Before he had finished speaking, a large part of the audience was outside

and racing to Vineyard Haven as fast as horses would carry them."

The New York Times added that "Nearly the entire population of that

place hastened to the scene." The Cottage City Fire Department started

for Vineyard Haven at about 9:30 p.m.

A "brisk northeaster" was blowing the night of the fire. Gale-force

winds gusted to near hurricane strength by midnight.

The New Bedford Evening Standard wrote:

"The wind at the time of the fire was from northeasterly, and blowing

thirty miles an hour. When the fire was burning most furiously on the west

side of Main street, it veered to northward, and helped to check the progress

of the flames in that direction; and later, when the Mansion House and

buildings in that vicinity were burning the hottest, it changed more to

the east, and enabled the people to save the house toward the foot of Beach

street.

The August 1933 Gazette anniversary article noted:

"The night was thick and there was a little drizzle which did not

dampen the flames. Wind roared through Main street, and fire leapt from

block to block and from roof to roof."

The light of the fire was plainly seen in New Bedford, their newspapers

reported.

The Boston Globe wrote:

"The fire was plainly visible to many of the cape towns, though at

first they were not able to locate it. It was very plainly to be seen from

Cottage City and other parts of the island, it being thought at first by

citizens of Edgartown that Cottage City was burning."

The Boston Evening Transcript asked:

"Who would have said that old Holmes's Hole would have been swept

away by a fire before the crowded 'cardboard' Cottage City on the bluffs

of Martha's Vineyard?"

Left-to-right: The

alley between Jenkins' shop and Eleanora Luce's home; the ruins of Jenkins'

Paint Shop; the ruins of Crocker's Harness Factory; "Scovy Duck Alley"

south of the factory.

Left-to-right: The

alley between Jenkins' shop and Eleanora Luce's home; the ruins of Jenkins'

Paint Shop; the ruins of Crocker's Harness Factory; "Scovy Duck Alley"

south of the factory.

The August 1933 Gazette anniversary article noted:

"The late N. Sumner Myrick, staying at Cottage City at the time, was

correspondent for the Boston Herald, and scored an able beat for his paper.

He roused out the telegraph operator at Cottage City, started him with

sending material, and then managed to get to Vineyard Haven. A clergyman

with a horse acted as messenger, taking copy through the night from Vineyard

Haven to the telegraph office in the other town.

The Boston Sunday Herald published this story the morning

after the fire:

A CARNIVAL OF FLAMES.

The Town of Vineyard Haven Destroyed by Fire.

Between 40 and 60 Acres Burned Over.

Intense Excitement at Cottage City

(Special Dispatch to the Herald.)

VINEYARD HAVEN, Aug. 11, 1883. At 9 o'clock this evening

an alarm of fire was sounded in this village, spreading consternation among

all its people. A severe northeasterly storm was blowing, and the direful

consequences were easily understood by the frightened villagers, who were

aware of the utter lack of apparatus for the extinguishing of a conflagration.

The fire was found to be in the harness factory of R. W. Crocker, where

it is supposed to have originated near the boiler. Almost immediately the

whole structure was in flames, and, fed by the favoring wind, the fire

began its devastating march through the town. In quick succession the fire

caught the barn of Frank Vincent, Frank Norton's house and fancy store,

John Holmes' house, the dwellings of William Douglas, Dr. Brown, Charles

G. Luce, Clarinda Chace, Mrs. Crocker's home and store, and the houses

of Peter Manter, Mary Ann Daggett and Mrs. Cynthia Chace. At 10 o'clock

the fire had progressed well across the main street and stood a good show

of sweeping the southern part of the town. The only means of checking it

were the primitive buckets, and these seemed impotent indeed. The whole

village was 'on the move,' and the streets were crowded with the effects

of homeless people. Everything was excitement in the intensest degree.

At 10:30 o'clock the grocery store of Stephen C. Luce, Wendell Crocker's

grocery and dry goods store, Peakes' house, occupied by George N. Peakes,

the houses of Mrs. Alice Merry and John H. Lambert, the Baptist Church

- all situated on the west side of Main street, and the house on the corner

of wharf and Main streets, were in flames, and the prospects at that hour

were that the whole south part of the town, and the greater part, including

the Mansion House, and all the surroundings would be devastated. A slight

rain was then falling. Soon after the alarm the whole of Cottage City,

including the useless fire department, was en route for the conflagration

and the excitement.

Was Visibly Increasing

At 11:30 o'clock the fire had rushed down both sides of

Main street, sweeping everything in its path. John Lambert's dry goods

store on the west side, next to the Baptist Church, and the following buildings

on the south, were then on fire: Luce Bros.' country store and Masonic

Hall over it, the fancy store of John Lambert; William Hammond's barber

shop, with home in the rear; Samuel Luce's jewelry store; J. H. White's

tin shop; Lorenzo Smith's new store (not finished); J. F. Robinson's grocery

store and Hatch's express office. On the east side, in addition to those

named in the first part of this dispatch, Blish's jewelry store, Thomas

Tuckerman's store, Ellis Manter's printing office and boot and shoe store

combined, Dr. Lane's office, in the same building, a house owned by Dr.

Leach and occupied by John Conroy, Leavitt Norton's residence and a large

new house (unfinished) were all in rapid course of destruction. The flames

jumped a long distance up the hill on which the village is built, setting

fire to the house of Capt. William Cleveland, on William street. The conflagration

at this hour also began to work up Spring street and the residence of the

Luce Bros. was soon enveloped in flames. The scenes and incidents beggar

description. The streets were filled with all sorts of personal property

over which the women and children, the old, the sick and infirm were lamenting

in a pitiable manner. At midnight the situation had become even more serious

than anticipated. Every store in the village was then on fire. The postoffice,

express office, livery stables, hotels - except the Grove Hill hotel -

all were in flames. Some 40 acres had already been burned over, and it

was expected that 20 more would probably be blackened ruins by morning.

The wind in the path of the flames was little short of a hurricane at 12

o'clock, thus adding to the moment's peril.

Situation at 12:30 O'Clock.

The fire seems now (12:30 o'clock) to have nearly defined

its limits. It is following in the direction of the wind, and in an hour

will very likely exhaust itself by burning to the fields south of the town,

known as the 'company place.' The Mansion House has just fallen, and a

house on the south side of Beach street owned and occupied by Julia A.

Worth; a small house next east, owned by the same lady and occupied by

Capt. Henry Dexter; Thomas C. Harding's house next west of Mrs. Worth's;

a house occupied by the widow of Matthew P. Butler, and the residence of

Minor Allen, chairman of the selectmen, are all in flames. Other buildings

burned on Main street, not previously mentioned, are Lucretia Luce's dwelling,

Jenkins' paint shop and Mary C. Dunham's dwelling. The old Lambert homestead,

on the west side, opposite the Mansion House, is now in flames, and upon

Spring street, Gilbert Brush's house and the ice cream saloon of Benjamin

Dexter are the latest acquisitions to the conflagration. The hooks and

ladders brought by the firemen from Cottage City have done splendid service,

and much valuable property has been saved by their energetic aid. Indeed,

Cottage City has lent a helping hand generally to her distressed neighbor.

The loss is variously guessed at, but $200,000 will be pretty nearly correct.

This is far from stating the actual loss to the village. The dwelling houses

destroyed were not more than half insured, and they were owned and occupied

by people who lived on their frugal savings, and who find themselves in

their old age deprived of the homes that have been their ancestors and

theirs for generations. The village will never recover from the blow, for

there is no business carried on to warrant an entire rebuilding. There

were about 250 summer residents in the village, many of whom were obliged

to flee precintately to places of safety.

Nothing But Ruins Left

2:30 A.M. - The fire is in its last throes now, and only

the flames from ruins of the burn district cast their lurid light on the

darkness of the stormy night. Freeman Allen's house on Beach street was

saved after strenuous exertions, as was also S. G. Bradley's harness shop

on Beach street. Capt. Grafton Daggett's home on the same street was also

among those destroyed. There was more or less thieving in a small way,

and the police were stationed on the road leading to Cottage City to intercept

the rascals who were getting away with plunder. There were no articles

of a serious nature that could be learned. The insurance cannot be determined

before morning, but it will be in the neighborhood of $70,000 probably.

The Quincy Mutual, it is understood, has quite a number of risks. It has

been quite impossible to give an entirely accurate description of the fire,

owing to a variety of circumstances, not the least embarrassing of which

is the fact that the nearest telegraph office is in Cottage City, three

miles from Vineyard Haven, and it was not easy to forward dispatches. The

list of buildings burned is correct, with possibly one or two exceptions. |

The Boston Herald followed up on their story a week later:

"Vineyard Haven has been stricken as but few New England fishing towns

ever were. If a calamity of the kind ever befell any of them, it was years

ago, while they were in the height of their prosperity, and when they were

able to meet disaster without succumbing. But Vineyard Haven was overtaken

when she had got pretty near the bottom of the hill, and when she was totally

unprepared. There could not have been a more perfect conjunction of unfortunate

circumstances than existed at the beginning of Saturday night's fire. In

the first place, there was no fire department, no organization of any kind,

no hooks, no ladders, 'no nothing.' And, as if this were not enough to

give encouragement to a conflagration, the buildings in the village were

mostly old and dry, and a severe northeast gale blew off the harbor directly

against the first building that took fire. The business and the greater

part lay before it. Everything was 'auspicious,' so to speak, for a great

fire, and yet, notwithstanding this, is the village had possessed any kind

of engine or head of water, or even anything as inconsequential as Cottage

City will doubtless someday have, the conflagration could have been staved

at the first corner. But insurance had been placed in an office where there

are no charges, the office of 'special dispensation,' and the result was

a loss of some 60 buildings and their contents, valued at $200,000, and

an appeal to the country for aid. And all this through the culpable, careless

indifference of the townspeople. Cottage City showed up well that night.

The fire department worked energetically and persistently, and in many

cases heroically. The young men composing it did all that could have been

done with what they had to do. With their hooks and ladders and two chemical

engines they undoubtedly saved thousands of dollars worth of property,

and had the village possessed fire apparatus of any kind, they would have

manned it to the incalculable advantage of the village people."

The cause of the fire has never been determined. Almost everyone attributes

the origin of the fire to be somewhere inside Crocker's harness factory,

although a 1931 Gazette profile of Foster Jenkins' widow, Mrs. Elizabeth

Carey (Harding) Jenkins (1843-1933), suggests that she was unclear whether

the fire started at the factory or in her husband's paint shop next door.

The Boston Globe wrote on Monday:

"The chimney attached to the engine which had been used during the

day was heated, and it is thought that the fire caught while the fireman

was cleaning out the boiler, though nothing can be definitely ascertained

on the subject. The floor around the boiler is cemented, but some oiled

waste used in cleaning was near the fire."

The New Bedford Evening Standard wrote:

"The cause of the fire is not known. A person was in Mr. Crocker's

shop at 8 o'clock, without a light, and saw no fire. There is a report

that the fire was caused by hot ashes thrown on a pile of leather chips;

and another that it might have been caused by a heated chimney in which

the soot had been on fire, and in which the fire might still have been

smouldering when the building was left for the night."

A later article in the same paper corrected this story:

"The origin of the fire remains a mystery. Mr. Crocker, proprietor

of the harness shop, says there could have been no burning chimney, for

no fuel but coal was ever used in the chimney; and the story about hot

ashes and leather chips thrown together is also incorrect, the ash heap

being thirty feet from the chip heap. There was a cement floor for three

feet round the boiler."

View southeast across

the ruins from the Methodist church tower. From left-to-right in the background

are the 1785 house (barely visible on the extreme edge of the left margin),

the Beetle/Roth house (which was torn down in the 20th century) and the

Great House (which was moved to West Chop in the 1920s.) The Lagoon is visible

in the distance.

View southeast across

the ruins from the Methodist church tower. From left-to-right in the background

are the 1785 house (barely visible on the extreme edge of the left margin),

the Beetle/Roth house (which was torn down in the 20th century) and the

Great House (which was moved to West Chop in the 1920s.) The Lagoon is visible

in the distance.

The villagers' reaction to the fire was frenzied and chaotic.

The Boston Evening Transcript wrote:

"The townspeople and their visitors were all engaged in packing up

and moving whatever could be moved to places considered remote from the

danger, only in a short space of time to have them destroyed or to find

it necessary to again and again move farther on. Teams were impressed into

service, and many women worked faithfully carrying water in pails, removing

and watching property, etc. The excitement was intense, and many 'lost

their heads,' causing much property to be destroyed which might have been

saved."

The Boston Globe wrote:

"The fire was not without its amusing incidents. One woman ordered

the men to desist from throwing the pillow cases and sheets out the window,

as they would get dirty, exhibiting an amusing presence of mind and thoughtfulness

in the face of the total loss of her property. On the Cottage City road

people were reclining on the roadside and seated in armchairs by their

property - seeing the hopelessness of putting out the fire by human effort.

They simply watched the progress of the flames and saw them die out this

morning.

The August 1933 Gazette anniversary article noted these

incidents:

"Women played a conspicuous part in fighting the fire. One of the

most extraordinary aspects of the disaster was the manner in which the

women of the town joined in bucket brigades and fought shoulder to shoulder

with their fathers, brother and husbands through the night.

"An eye witness said afterwards, 'The women! How

they did work. Why lots of the men (understand a great many men worked

like Trojans) stood around in the streets and didn't seem to know what

to do. They'd stand right by houses that were burning and not seem to think

of using water on them. Women had to crowd past them to get to the cisterns.'

"One woman found a man desperately tearing off a

door between two rooms. He said he was going to save it from the fire.

It took her some time to convince him that if the house burned, it wasn't

much use saving a door. Some householders saved the shutters from their

windows."

"One man was reluctant to part with a bucket, and

the would-be borrower discovered the reason was because $3,000 was hidden

in it.

The Vineyard Gazette wrote:

"Strange to say, many of those who came into town the night of the

fire, stood looking on, and did not render any assistance. It is but fair

to remark, however, that others worked very hard and lent a helping hand

whenever they could. Many women worked with the energy and endurance of

the 'sterner sex' till completely exhausted."

The Cottage City Fire Department, consisting of a hook and ladder company

together with their two new-fangled chemical engines, helped battle the

blaze, although reports were mixed as to their effectiveness.

The New Bedford Evening Standard wrote on Monday:

"The chemical engines and hook and ladder company from Cottage City

and a number of small force pumps owned by individuals did good service

in preventing the spread of fire across wider spaces of unoccupied land.

Where houses were close together, nothing could save them; even wet carpets

hung against the side of a house were but a momentary protection, the heat

of the flames drying and burning them after the briefest exposure."

"Almost the entire population of Cottage City was

on the ground, as well as mariners from vessels in the Haven, and many

of them worked well in fighting the fire. Capt. Benjamin C. Cromwell and

the crew of steamer Martha's Vineyard worked like Trojans, and it is due

to Capt. Cromwell's personal efforts that the house of William Harding

was saved, also one belonging to himself and occupied by Capt. F. W. Vincent.

One of the most efficient means of wetting buildings was the small force-pump

fitted to be set in a bucket and held steady by the left foot, while the

right hand works the pump and the left directs the hose. A great proportion

of the people were bewildered and crushed by the raging calamity, and could

do nothing but look on in terror and dismay. Others worked vigorously in

saving property, and many had their hands and clothing burned in their

daring efforts. Many women worked with great zeal and assiduity in saving

property."

The Standard followed up the next day with this comment:

"Mr. John D. Flint of Fall River, who worked on the roofs of three

different houses, states that not one of them had a ladder to go up to

the scuttle, and the only way to the roofs from inside was by building

stagings of trunks and furniture."

The 1933 Gazette anniversary article recalled:

"Capt. Cleveland found eight buckets in his well after the fire. Excited

individuals had tossed them in without having any ropes fastened to them."

The Standard added on Thursday:

"The Cottage City Star says on the night of the fire, when chemicals

were needed to be taken over to the engine sent from Cottage City, no team

could be found to carry them. The owners of horses who had worked all the

week would not think of letting them go 'way over' to Vineyard Haven to

save the town, if possible."

The Boston Globe reported on Monday:

"The fire department from Cottage City… exerted its utmost to

aid in stopping the conflagration, but the wind rendered its efforts of

little avail. Vineyard Haven, like many other country towns and some cities,

is a conservative place, and has been content to provide slight protection

against fire, in view of the fact that this is only the second fire in

nearly eighty years. The only available means of extinguishing fires are

water buckets and the line of men which the first settlers were wont to

use. The chemical engine from Cottage City was a pretty toy, but was only

an ornamental affair. It was almost useless at, any rate, after the fire

had gained much headway. The hook and ladder company, however, did good

service."

The New Bedford Evening Standard wrote on the 20th:

"Some exchanges have sneered at the Cottage

City fire engine, but Capt. Damrell says the fire would have spread and

destroyed $50,000 more property but for it.

Capt. John S. Damrell, former chief of the Boston Fire Department, happened

to be in Cottage City. The Globe wrote that Damrell "was gladly hailed

by owners of threatened buildings. He was given control by the town authorities."

The Evening Standard noted that "under his direction and good judgment

a wise selection was made of places to stand and fight the burning element."

(Damrell had been Boston's chief during its great fire of 1872, and later

was thought to have owned a summer home here.)

Some of the other volunteers on the scene were also looters.

The New York Times wrote on Monday August 13th:

"District Officers Innes and Seaver and Chief Dexter, of Cottage City,

organized a force to protect the household property which filled the streets

and vacant lots from the thieves, who made their appearance in large numbers,

coming mostly from the vessels in the harbor, and bodily attempted to carry

away the goods which had been saved from the flames. Several arrests were

made of persons caught stealing clothing."

The Boston Globe wrote:

"The presence of State Detectives Innes and Dexter was very fortunate,

as it prevented the theft of a good deal of plunder, but owning to the

confusion prevailing some goods were taken. A part of this was recovered,

however, and the thieves are known. Officer J. L. Dexter was called from

Cottage City, and a guard was placed on the Cottage City road to search

suspicious-looking parties. The fields and gardens adjacent to the burnt

district were heaped up with piles of furniture, crockery and other things,

which were anxiously guarded by the women of the distressed households.

The Boston Evening Transcript wrote:

"Hundreds remained on the ground all night looking after the goods

and household effects spread about out of doors."

The New Bedford Evening Standard wrote:

"Police arrangements were very defective, and a great deal in the

way of moveable goods and chattels was stolen. No one would have been blamed

if the thieves had been shot dead in the midst of their work."

The 1933 anniversary article in the Vineyard Gazette

wrote:

"Henry A. Edson of Brockton and Edgartown recalls the night of the

fire vividly. With a companion, he went to the scene and worked diligently

in helping to save things. Sparks were flying and several volunteers salvaging

the stock of a clothing store put on jackets to protect their clothing.

But one bystander went further, and Mr. Edson recalls that he was arrested

later and that four pairs of trousers were found on him. Mr. Edson recalls

entering the basement of the Mansion House and eating pie while the roof

crackled and burned overhead. Finally deciding that it would be safer outside,

the boys took up what pies they could carry and went out. But as soon as

they reached the sidewalk the pies were snatched from them and eaten by

others."

The New Bedford Evening Standard wrote on Tuesday August

14th:

"Since the fire, District Policeman Henry A. Dexter and George H.

Innis, with Messrs. Jason L. Dexter and Eli Leighton, of the Cottage City

Police, have been looking after stolen goods, and they have found from

$250 to $300 worth of silver-ware taken from John H. Lambert's store. Besides

places on shore, four vessels in the Haven were visited, and on board one

was found a pair of boots, a miniature portrait of Mr. Lambert's father,

and some other articles."

View east

across the ruins from the Methodist church tower. Church street ("Franklin

street") is in the right foreground, and Union street ("Wharf

street") is in the far right background. A crowd has gathered in the

alley south of Crocker's Harness Factory, near the center of this photo,

where the fire began. The 1785 House can be seen on the extreme right. Photo from the 1954 Renear's Garage calendar, courtesy Bob Renear.

View east

across the ruins from the Methodist church tower. Church street ("Franklin

street") is in the right foreground, and Union street ("Wharf

street") is in the far right background. A crowd has gathered in the

alley south of Crocker's Harness Factory, near the center of this photo,

where the fire began. The 1785 House can be seen on the extreme right. Photo from the 1954 Renear's Garage calendar, courtesy Bob Renear.

| William I. Ward, D.D., a pastor of the Vineyard

Haven Methodist Church at the time of the fire, was profiled in a 1930

Gazette article in which he shared his memories of the fire:

"The historic fire occurred during the second year

of his stay. Dr. Ward and his wife lived on William street between Center

and Spring. It was on a Saturday night, and the couple were preparing for

bed when the church bells rang, the common alarm for fire. Going to a window

the doctor was able to smell the odor of burning leather and knew that

the harness factory was on fire.

"Three buildings stood close together on the approximate

site of the present bank and hardware store, the harness factory, a paint

shop and a livery stable. In a very few moments they were all three a mass

of flames, fanned by a northerly wind that carried clouds of burning shingles

over the roofs of the remainder of the town, and swept graves waves of

heat against adjoining buildings to ignite them almost instantly.

"There was no water system at the time, in fact there

were very few wells, many people depending on cisterns for their water.

There was no fire apparatus, although a chemical cart was brought from

Oak Bluffs and used with good results as long as the supply of chemical

lasted.

"It was an awful night, as the doctor recalls it.

The fire, sweeping down Main street, burned the heart out of the town.

All but one place of business was destroyed, and the fire backed up into

the side streets, reaching a number of buildings at first thought to be

out of its path. As the doctor moved about here and there, he saw much

that was humorous, tragic and saddening, for although no one was injured,

many lost all their possessions.

"One merchant, whose house was far from the danger

zone, came down to look at his place of business which the fire had not

yet reached. He found the door open and various men inside helping themselves

to the stock from the shelves. He offered no objection, but smiled and

went away.

"One house caught fire at the rear and the owner

asked for help to remove a piano from the front room. The piano was too

large to go out through the front door, having been brought in from the

kitchen. The men suggested knocking out a window, but the householder forbade

it, and house and piano went up in smoke. Another man stood in his doorway,

throwing crockery into the street, every piece smashing as it landed.

"A family, realizing that their house was in serious

danger, set about packing articles that they wished to save, piling them

into a large chest. When the chest was filled, the house was on fire, and

they then discovered that the chest was too heavy to be moved and it had

to be left for the flames to destroy.

"Ben Dexter, an eccentric wood carver, who had a

shop near Main street, had made many grotesque human figures, in life-size,

which he had standing outside his shop. The building caught fire and the

figures also, burning to ashes. Persons who saw them, not knowing what

they were, thought that they were actual people, burning alive.

"In the midst of this tumult of destruction Dr. Ward

realized that the flying embers were endangering his own home, and he hastened

there to find that burning shingles were indeed falling on the roof from

time to time. With considerable difficulty and not a little danger, he

succeeded in reaching the roof, taking a bucket of water and a dipper with

him. Seated on the roof, he threw water in each shingle as it landed, thus

saving the house. Once, as he threw a dipper of water, he lost his balance

and started to slide down the roof. Had he fallen, he would have undoubtedly

been seriously injured, but luckily, he was able to check himself and retain

his former position.

"During a sort of lull, when no embers were falling,

the doctor sat resting on the roof when a group of men passed. As they

looked up they could see the doctor sitting there, by the glare of the

fire behind him. 'Get down from there, you lazy devil, and help put out

this fire!' they called.

"The Methodist Church, being out of the path of the

fire, escaped unscathed and made an excellent repository for furniture

saved from burning homes. The next morning an elderly man who had slept

through the fire and knew nothing about it, arrived at the church without

having seen any sign of the destruction of the night before. Opening the

door he stared at the stacked furniture, dumbfounded. Turning to Dr. Ward,

who was near, he said: 'I suppose they'll get this out in time for us to

go in for services?'

"'I doubt if anyone attends services today,' replied

the doctor.

"Serious as the loss was, the town was practically

rebuilt before the doctor left a year later, the buildings springing up

like mushrooms, larger than before, and in many cases better located."

|

The fire was finally under control by about 2:30 or 3:00 a.m. Sunday

morning. When dawn broke, the scope of the destruction was clear.

The New Bedford Evening Standard wrote on Monday:

"The village of Vineyard Haven presented a sad appearance. The smoking

ruins, and the piles of wet and dirty household goods and other articles

strewn in every direction were enough to evoke the warmest sympathies.

In some places, in buildings, the effects of many different individuals

were mingled in the greatest confusion. Many aged persons and others lost

all except the clothes they had on."

The Boston Herald wrote on Monday:

"When daylight broke this morning, it found about 60 acres of the

village of Vineyard Haven a mass of smouldering ruins, out of which arose

scores of blackened chimneys, standing as silent monuments of desolated

homes. It is many a day since the village had contained as many people

as it has today. Crowds poured in from all portions of the island. Many

came to offer assistance, but the majority merely to gratify curiosity.

Cases of extreme hardship are coming to light. The wife of James Davis

died during the night from the effects of fright. Some of those who were

homeless after the conflagration had saved nothing whatever of value, but

were left entirely upon public charity."

The Boston Globe wrote on Monday:

"The ruins are smouldering still, and are eagerly being raked over

to find whatever may have withstood the heat of the flames."

The Boston Evening Transcript wrote:

"Sunday morning early thousands visited the place, though the day

was black and damp, and all day long, amid the gloom of the stricken town,

wandered about, gazing at the spectacle of devastation. … The village

is a sad sight, and is being visited by thousands of strangers from Cottage

City and from all parts of the island."

The plank sidewalks had all burned, exposing the gutters underneath.

The Standard noted that "pedestrians have to wallow in an ashy ditch

or take to the middle of the streets."

There was one human casualty - elderly Mrs. Emeline B. Davis, whose house

was lost in the fire, died during the excitement, perhaps from a heart attack.

Some livestock was lost. A roasted pig was found near the foundation

of Crocker's factory, and two more dead pigs were found burned under Capt.

Vincent's stable next-door.

The New Bedford Evening Standard added on Tuesday:

"One of the sad sights about Vineyard Haven is the tribe of homeless

cats. A dog follows his master, and is at home where the master is at home,

but a cat generally becomes more attached to her dwelling than to any person."

About fifty acres had been burned, containing more than sixty buildings.

The loss was estimated by the insurers at between about $190,000 and $196,000,

of which only about $62,000 - 64,000 had been insured.

The Vineyard Gazette wrote on August 17th:

"The entire business portion of the town of Vineyard Haven…was

totally destroyed.…Twenty-six stores, thirty-two dwellings, two stables

and twelve barns and smaller buildings were burned. Desolation is abroad

in the streets. Some of the sufferers have lost all; others have an inconsiderable

insurance."

Charles Banks later wrote in The History of Martha's

Vineyard:

"When the last embers had died out it was found that the Baptist meeting-house,

32 dwelling houses, 26 stores, 12 barns, and 2 stables had been burned

to the ground. A damage more irreparable was done to the beautiful shade

trees on the Main street and others covered by the burnt district, as these

noble trees were all killed by the flames."

Henry Franklin Norton wrote in his 1923 book Martha's

Vineyard,

"Sweeping southward it burned every building on both sides of Main

street as far as the old Luce house just above the fountain. In another

direction it went as far as the Bradley house, and on both sides of Beach

street as far towards the shore as the Branscomb house. The fire destroyed

property covering an area of over forty acres. Seventy-two buildings were

consumed, with a loss of over two hundred thousand dollars. This was a

terrible blow to the community, but rebuilding was commenced at once. However,

many beautiful old trees and the houses of 'ye olden time,' filled with

family treasures and curios from all parts of the world, were destroyed."

Jenkins' paint shop (including the old Masonic Hall) was valued at $2000

- 2500, and the paints and other stock inside the store at another $2000

- 2500. He was insured for a total of only $2000. The 1931 Gazette profile

of Foster Jenkins' wife remarks that only the key to the paint shop and

the office safe were saved. (See Part One

for more on Jenkins' shop and Crocker's first harness factory.)

Crocker's factory, together with the two tenements he had to house his

workers, was valued at a loss of $3000. The machinery and stock lost inside

the factory were valued much higher - at $20,000, the largest single monetary

loss in the fire. He was insured for only $10,000 - less than half its value.

Hundreds were left homeless. Islanders were quick to open their homes

to those in need. Thousands of dollars were quickly raised at charitable

events, a large portion of the money coming from Cottage City summer residents

and former Vineyarders who had prospered off-island.

Not all the gifts were monetary. The Standard reported: "W. W. Evans,

civil engineer, of New York, has sent a Winter's supply of under garments

to three of the elderly men who lost everything in the conflagration."

The Boston Evening Transcript wrote:

"The people of Vineyard Haven are beginning to realize their sad condition.

The homeless are looking about for new places of shelter. On Sunday the

people were sheltered through the storm by kind friends, who are charitably

disposed. Yesterday the stern realities of the situation were impressed

upon those who find everything lost, and the demand for homes and bread

still upon them.

The Boston Herald wrote:

"Rev. Mr. Gushee of Cambridge stated that there were 75 people thrown

out of employment from R. W. Crocker's harness factory, nearly all of whom,

with their families, were in a destitute condition. There were also eight

or ten widows who were in a distressing situation, and altogether some

400 or 500 people were turned out. A number of aged sea captains, who had

once been in comfortable circumstances, but were in reduced means previous

to the fire, were now penniless. One of them he knew had not more than

$5 left from the flames. Twenty thousand dollars, he thought, would not

be more than enough to place all these people in circumstances to live,

even."

The New Bedford Republican Standard wrote:

"The night of the fire, Dr. Leach accommodated twenty-seven persons

with lodgings in his house. Others accommodated others. It cannot be expected

that this can continue."

"A gentleman who was burned out at Vineyard Haven, rolled out of his

store some barrels of flour and a tub of butter, which were burned. He

retreated to his own unburned dwelling, bearing in his arms as the only

effects saved, a few bottles of Hunt's sarsaparilla, and a small box of

one cent thimbles, with a few other trinkets - a small dividend."

The Vineyard Gazette wrote:

"Our people who were so fortunate as not to be burned out of house

and home have been very hospitable and thrown open their doors to those

who needed shelter, and many acts of kindness have been rendered which

will long be remembered by those who were in need of assistance."

The New Bedford Evening Standard wrote:

"Forty families or more are turned out, and nearly twenty have nothing

left but a house lot; and some who lived on hire not so much as that. Some

saved a little furniture, and some saved not enough to furnish one room.

Many who were not burned out, have suffered considerable loss by breakage

in moving their effects out and having them wet. Their goods were hurriedly

loaded and more hurriedly dumped in the fields or the woods. Among those

who are left nearly destitute are the families of Mrs. Mary Ranier, Mrs.

Alice Merry, Michael Conroy, Peter Hooper, Cynthia Chase, Capt. Thomas

C. Harding, Benjamin Merry, Sawyer B. Swain, Mrs. Matthew P. Butler, Mrs.

Blish, and William H. Hammond. Many of these are people quite well advanced

in years, who can hardly expect to again possess homes of their own."

View toward

the intersection of Church street and Main street. Photographed from the

old Dunham property, where Rainy Day is today. The ruins of the factory

and the paint shop are behind and to the left of the two burned trees.

View toward

the intersection of Church street and Main street. Photographed from the

old Dunham property, where Rainy Day is today. The ruins of the factory

and the paint shop are behind and to the left of the two burned trees.

Ad in the

Aug. 16th New Bedford Evening Standard

Ad in the

Aug. 16th New Bedford Evening Standard

Tourists flocked to the ruins from all over the island and the mainland.

The Boston Globe wrote:

"The ruins at Vineyard Haven are visited by crowds of eager relic-hunters

and others, who, out of curiosity, come to view the scene of Saturday night's

fire."

The Vineyard Gazette:

"Never did so many people visit the usually quiet village of Vineyard

Haven as during and since the fire. … Those relic hunters must have

taken a grim delight in carrying off anything found among the ruins that

did not belong to them."

The Republican Standard:

"The Monohansett carried quite a party to Vineyard Haven this afternoon

after the arrival of the Martha's Vineyard. The cheapness of the excursion

and the beauty of the day enlarged the party."

The New Bedford Evening Standard:

"The scene of the recent fire at Vineyard Haven still continues to

attract many visitors from Cottage City, comers for a day only generally

improving a part of the time by a visit to the Haven, all of which makes

good business for the stable men. The drive itself, for the greater distance

over a fine concrete road, is a very pleasant one, and as one approaches

the pretty little town, embowered in trees, on the hillside, there is little

to tell of the fire. When the town is fairly reached, however, the scene

is desolate enough. Here and there some object tells of the home that occupied

the blackened spot only a few days ago, - now a charred chair frame, now

the remains of a cook-stove, but for the most part even these mute witnesses

are absent and only a little pile of chimney bricks and debris remain.

Relic hunters continue to peer about among the ruins, in search of some

object that will serve as a memento of the fire."

"Two ladies burned out at Vineyard Haven actually had to pay, in order

to get breakfast Sunday morning, $6 fare to Cottage City and return."

The New York Times:

"The village is a sad sight, and is being visited by thousands from

all parts of the island and from the mainland. … Thousands of people

visited the scene of the fire in Vineyard Haven on Sunday, and all day

long wandered about gazing at the spectacle of devastation."

The New Bedford Evening Standard:

"Hackmen charged $1 each to take people from Cottage City to Vineyard

Haven Sunday, and hacks never carried so big loads of people before."

"The bell of the Baptist Church tolled as it fell, and was broken;

yesterday [Sunday], hunters for relics broke it into small pieces, all

of which have been carried away."

The future of Vineyard Haven looked very grim during the first couple

of days after the fire. Many newspapers expressed their pessimism:

The Boston Globe, Monday, August 13th:

"The village will never recover from the blow, for there is no business

carried on to warrant an entire rebuilding."

The New York Times, Monday, August 13th:

"The fire strikes almost a death-blow at this ancient village."

The New Bedford Evening Standard, Monday, August 13th:

"Doubt is expressed as to the rebuilding of many of the structures

which were consumed; and the loss is a very serious blow to town."

However, the local outlook quickly improved. Rebuilding started immediately

in an unexpected rush. Newspapers quickly revised their predictions. Charles

Banks wrote in The History of Martha's Vineyard "With characteristic

energy Mr. R. W. Crocker, the proprietor of the harness factory, began work

on a new structure while the unburnt timbers were yet smouldering, and others

followed in quick order. The quaint street had vanished, but a new line

of buildings soon arose on the old thoroughfare."

New Bedford Evening Standard, Tuesday August 14th:

"The ruins at Vineyard Haven do not look so gloomy as they did yesterday.

The chimneys were tipped over this morning, and this finishing of the destruction

took off the monumental characteristics of the sad picture. People who

have lost all or nearly all have resumed much of their wonted cheerfulness.

The results are not so serious as a check to the prosperity of the village

and town as were at first anticipated."

The Vineyard Gazette, August 17th:

"It was remarked soon after the fire that

Vineyard Haven would never be rebuilt, but the 'sound of the hammer' indicates

the march of improvement already inaugurated. Several lots have already

been sold, new buildings will soon tower over the ruins - but doubtless

it must take time for the entire burnt district to be rebuilt, and many

people must suffer greatly by the dire calamity."

The Boston Herald, August 19th:

"We predict that Vineyard Haven will be rebuilt and much improved

in appearance before next summer."

Another

view southeast across the ruins from the Methodist church tower. Union Street

is visible on the left.

Another

view southeast across the ruins from the Methodist church tower. Union Street

is visible on the left.

Another view

from the Methodist Church Tower, showing the intersections of Church, Main,

and Union.

Another view

from the Methodist Church Tower, showing the intersections of Church, Main,

and Union.

Looking

northwest across Main street. The bottom of Church street ("Franklin

street") can be seen between the two wagons.

Looking

northwest across Main street. The bottom of Church street ("Franklin

street") can be seen between the two wagons.

This is an unfinished draft! Do you have any memories of any of

the other people, places, businesses or events mentioned here? Or do you

have corrections, additions, or suggestions? Please contact Chris Baer <cbaer@vineyard.net>

< Return to Part One: Crocker's

First Factory <

> Continue to Part Three: Crocker's Second Factory > Under Construction

Return to The Bank to Union Street

Return to Tisbury History

Part of the aftermath

of the 1883 fire. This photo was taken from the location of the modern

Linden Tree, looking northwest.

Part of the aftermath

of the 1883 fire. This photo was taken from the location of the modern

Linden Tree, looking northwest.